© Mary Woodbury

Mary’s LinkTree. Author of the Back to the Garden, The Stolen Child, and Bird Song: A Novella.

I was just a teenager when Pappaw died and just over a month later, Mammaw died. I can’t remember whose funeral it was when I learned about the pine trees. I do remember my mother’s toughness back then, with two parents dying about a month apart. The second funeral happened on Mom’s birthday. She drove us four kids, including the youngest at just around two months old, from Chicago to eastern Kentucky. Dad would fly down the next day from his business trip.

We’d made this trip often since I was born. My dad’s parents lived in Louisville and my mother’s near Hindman, so we traveled down to see them every holiday and summer. I grew up loving Kentucky. My experiences spent there, especially in the lonely hollers of Appalachia, designed who I became as an adult and were life-affirming. I clutch these bittersweet memories, sometimes wishing I could go back for just a day. The last time I visited Hindman was in 2012 on a family road trip—though we’ve also been to neighboring Tennessee a few times since, where my cousins still live. When traveling to the Gateway to the South, we would pass through the familiar cornfields of Indiana and drive across the exciting Ohio River bridge, landing in the next state, Kentucky. Louisville, also my birthplace, seemed crowded and smoggy like the Chicago area we’d come from. Slugger Field was the most fun sight until Cherokee Park, and then came one of our favorite things, the tunnels leading to the country. After the tunnels, small cliffs rose on the edges of the highway, leading to the rolling green hills and bluegrass of central Kentucky’s horse country. Later we’d reach the solitude, peace, and otherworldly atmosphere of the Appalachians.

I don’t recall the funerals as much as I do the burial ceremonies and all-night wakes. Both burials took place at an old cemetery that has since been modernized; back then it was full of long grasses, goldenrods, wild columbine, and asters and seemed impossibly far from any civilization. I always felt I was going back in time when visiting the Appalachians. Dad took me aside at one of the funerals and pointed over to a ridge beyond. “See those pine trees on top of those mountains? Your mother planted them when she was in grade school.” The trees were now nearly 40 years old, I thought. I imagined her planting the trees years before and knew that similar pines covered the mountain behind my grandparents’ house. My main activity when younger was climbing one hill after another, scrambling for hours to get to the highest point I could. I’ll never forget that day at the cemetery, though. I had no idea Mom had helped to plant those trees and was intrigued. I learned much later from Mom that Dad’s mom and aunts belonged to Delta Theta Tau in Louisville, which was the organization helping to fund her elementary school near Brinkley, KY, and which also funded the tree-planting program. That was, of course, long before she met Dad. Small world.

Also, much later, when I lived in British Columbia, our last camping trip before moving to Canada’s east coast was at Salt Spring Island. I was surprised to learn, in my dreaming of the Appalachians and when I fell in love with the band Rising Appalachia, that one of their songs was filmed on Salt Spring. Most of the band’s videos, though, were filmed in the Appalachians and reminded me of younger times. More innocent times. Times in the hills, creeks, and wildflower meadows of eastern Kentucky. Transposing past and present, from Hindman to Salt Spring Island, came another coincidental “small world” reminder. I wrote about the band and some of my memories at Climate Cultures.

I’d been in tune with the changes in the world since Pappaw’s stories about his coal-miner days, before he became a carpenter. Many changes in eastern Kentucky have not been good news: poverty, meth, pollution, continued extraction of fossil fuels—the sludge of modern America’s journey to false riches, false idols, and false news. But, beneath all of it remains a resiliency of people, with the acknowledgment of culture (music, food, poetry and other writing, protests, protections of the land), which holds dignity and strength together in a kind of beautiful journey that ties in well with the freedom and beauty I found among those pine-covered hills of my youth.

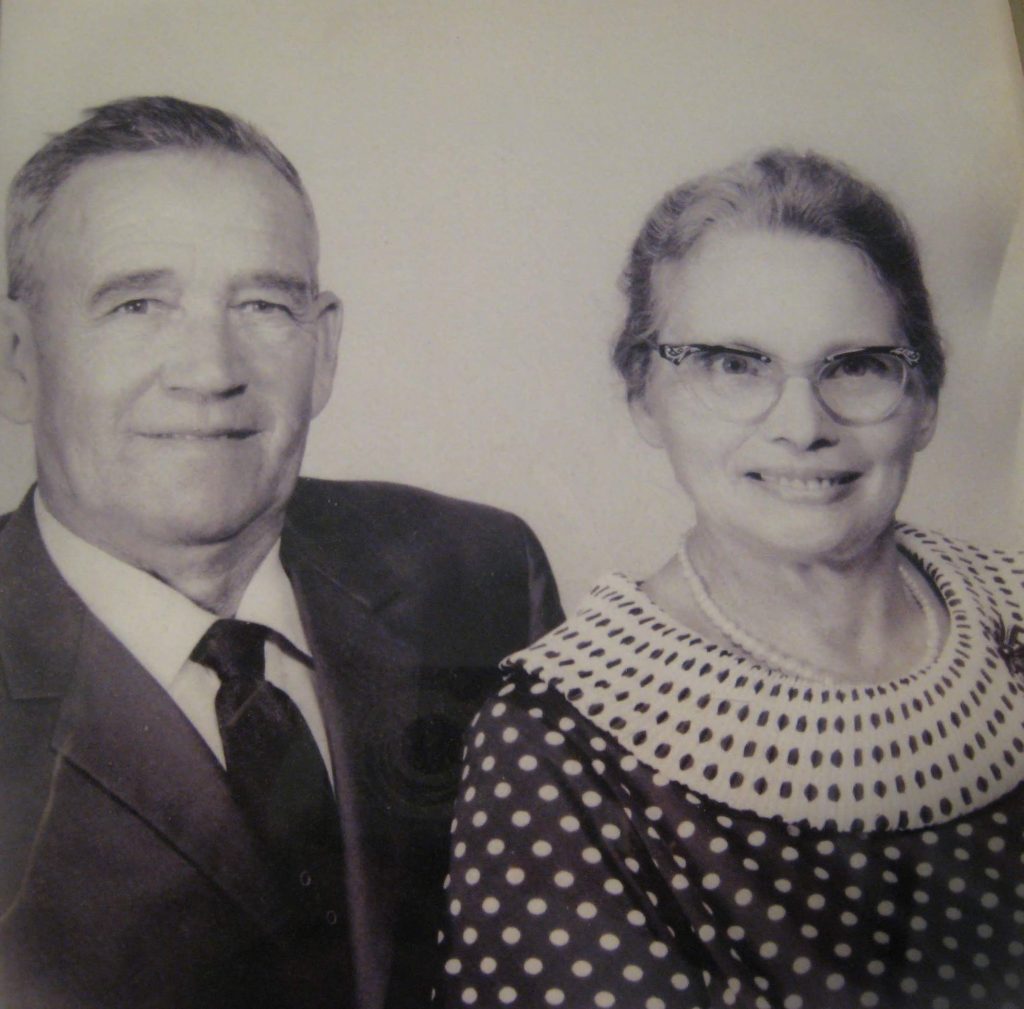

The backbone of my Collins-Gibsons ancestry may well be explained in that old joke about newcomers to America and the kinds of structures they built. The English built a church, the Germans a barn, and the Scot-Irish a whiskey still. My mother told me stories about how when she grew up and how some of Pappaw’s relatives liked their moonshine. And I like my bourbon, too. But, something about the resiliency of Mammaw and Pappaw rings true to Kentuckians to this day. Not having an education past grade-school, Pappaw taught himself all the things. He was a jack-of-all-trades and built their house in the hills, including the electrical and plumbing parts. Mammaw and Pappaw both lived off the land as they were kids of poor Kentucky coal miners and farmers. Self-taught and survivalists, today they, and many like them, would probably be social media influencers. They grew vegetables and grains, raised and killed chickens with their bare hands, made their own quilts out of old clothes, churned their own butter, and, my favorite, dried beans for making shucky beans. What was just a way to preserve vegetables before they bought a freezer also happened to also be the most tasty way of preparing and cooking green beans. As I write this, I am drying out beans from my garden to make that old recipe.

During these visits, we would be lucky to see any snow during Christmas, when we would always go up to the mountains with my cousins and older relatives to chop down a tree for decorating. Up in the mountains, reached by an ancient dirt road, the air seemed thin and cold. Something about the mountainscape encouraged fog, echoes, and mysteries. My cousins had me convinced a witch lived in an old shack we’d see on the way to get a tree. So many backroads back then were full of tiny clapboard shacks, some with broken windows. On those Christmas tree hikes, the grasses dried and crunched under our feet. But summers and springs were pleasantly warm and perfect for climbing the hills, exploring creeks (yes, we called them cricks), and finding fascinating old cabins, rivers, wildflower meadows, and people older than dirt down the many hollers. Our parents would tell us to not go up into the mountains, due to copperheads, but we did anyway. Mom told me later she did the same thing as a child. She would climb all day and get in trouble if she went too far. Like mother, like daughter.

Eastern Kentucky summers were full of wilderness compared to our home in Chicago. We’d jaunt down the holler to pick black walnuts at an old lady’s house at the end of the trail. Flanking the holler on one side was a creek and on the other a mountainside that had tiny waterfalls in the summer and icicles in the winter. When we went back in 2012, that dirt holler had been expanded into a paved road, flattening that part of the mountain, including those tiny cliffs. The creek was no longer there either, though I don’t know how a creek just ups and disappears. I imagine developers did some landfill so that modern houses could be built. The previous black-walnut lady’s house was gone, and the road extended further. We couldn’t even find the familiar access to the mountains, which had been our previous starting point when hiking uphill. The cemetery was modern and well-mowed. New houses and kudzu had replaced our holler. I know that time changes things, but Mammaw and Pappaw are long gone, along with their holler and part of the mountain behind them. I was surprised to see their house still standing.

Pappaw had been born and raised in a log cabin on Troublesome Creek, which flooded this summer. In 2009, 5 inches of rain fell in a 24-hour period in the mountains. By 2020, eastern Kentucky was becoming more prone to flooding and had experienced consecutively wetter seasons than before. By late July this year, a flash flood in the Hindman area, along with other Kentucky towns, became one of the most extreme in the state’s history. Within 48 hours, 8-10 inches of rain fell, followed by 4 more inches a couple days later. The floods are related to climate change, simply because warmer atmospheres hold more water. But the mountainous topography also aids the problem due to water moving down to valleys. The area around Hindman is also surrounded by mountaintop coal removal. The removal affects landscapes, and stripped mountains aren’t as protective as mountaintops and sides with healthy soils and forests. All these things in tandem helped produce the catastrophic flooding, in which 37 people died.

I called Mom and asked if she had heard. She had been watching it on television, and though we don’t have cable channels, I found some reporting online. Mom worried about her friends. She’d been back to her Hindman High School’s 50th reunion not too long ago and said she couldn’t reach anyone. I’d had my eyes and ears tuned to the happenings in the area for years. I was happy to find things like Rising Appalachia, Mountains Piled Upon Mountains (anthology), the Blackjewel coal miners’ protest, and more, which all are evidence of the same kind of Appalachian resiliency I found in the poverty-stricken area of my mammaw and pappaw’s times. If someone else was hurting, my grandparents and other neighbors would be on the spot to help. Though poor, they—and the community around them—helped others get by. Now I tuned into the news and watched the rising waters, the devastation, the deaths, and the incoming heat wave. Governor Andy Beshear was great at gathering help for everyone. A lump welled in my throat, both at the deluge and destruction of one of my favorite places in the world as well as the courage of residents helping each other. State and national parks offered housing. Beshear visited hard-stricken areas and provided information on where to get water, food, clothes, and shelter. The community, even if someone had lost their homes, was out doing boat rescues, offering provisions and help.

I long to go back there for another visit. Our last trip in 2012 was punctuated by invasive kudzu, a lack of Piggly Wigglys (which to a child was fascinating), and a heatwave across the south. Even in the mildly warm summers I remember of the mountains, now it was around 100 degrees during our entire road trip. We camped in Daniel Boone State Park and sat outside on the cabin porch at night just to get some kind of fresh air. I still call eastern Kentucky “home” when thinking of places I was raised. My next novel is based upon the area, so I guess that’s my way of traveling back for now. I’m not sure the home I remember still exists, at least the physical landscape. But I would like to think that surely, I could find a wildflower-flanked holler, a patch of halfrunner beans, a clear-running creek, the sound of a nightingale while sitting on the front porch in the evening while someone’s pappaw whittles and tells old stories to his granddaughter, an old bluegrass ballad being played in the distance, and a mountain still intact, maybe even with pines my mother planted.

While Mary Woodbury spent memorable holidays and summers in the Appalachian holler where her grandparents lived, she now lives in Nova Scotia with her husband and two cats. Under pen name Clara Hume, she has written the Wild Mountain Series: Back to the Garden, The Stolen Child, and Bird Song: A Novella. Mary contributed to the book Tales from the River and edited the anthology Winds of Change: Short Stories About the Climate (2nd ed., 2022). She is a graduate of Purdue University, with degrees in English and anthropology. She and her husband maintain a two-acre property with beehives, over 40 newly planted trees, and much more. You can read more about her at her blog and watch videos of her meadow cam at YouTube. Mary explores world eco-fiction at Dragonfly.eco and has interviewed many of the major authors in the field.